This blog post is very detailed and long. This blog provides background information and an explanation of flexibility methods based on scientific research. There’s a lot of science and medical geekery in there. If you don’t want to get into all that, and just want to find a specific area of the body, please click on the table of contents to jump to the section.

In Begining

A few topics are frequently discussed in the sport of gymnastics. The most talked about topics include drill progressions to improve skills, strength, conditioning, dealing with injuries or pain, and managing fears.

In my 25 years as a gymnast and coach, and as a sports physical therapist who sees hundreds of gymnasts each year, flexibility has been the topic I have received the most questions. It’s a good thing too. To be able to safely and correctly perform gymnastics skills, you need to have a lot of flexibility. It is also a key component of scoring that judges use during competitions. If flexibility is not practiced regularly and properly, it can be a problem that hinders an athlete’s ability to improve or even lead to increased injury risk.

Offering flexibility advice has been a key part of my job, as well as treating and consulting in all aspects of gymnastics worldwide. It can be exhausting to find the right information and apply it to your practice to see long-term results in the gym, given the amount of information available online, the rapid progress of scientific literature, and the many possible reasons why flexibility is a problem.

I meet many well-intentioned gymnastics coaches and parents who are simply looking for easy use, but scientifically-backed flexibility program to help the gymnasts they know to increase their flexibility, reduce the risk of injury, and increase their performance.

Many people tell me they have tried searching the internet, visiting clinics and camps, and asking for help at gyms, but were overwhelmed. They watch videos on the internet, practice stretching at home and in practice, but they don’t succeed. I have heard them tell me that they sometimes make temporary progress but that nothing lasts long-term and shows up in their skills. They usually give up after a few months and just say, “He/she is just inflexible, they have poor genetics.”

This leaves gymnasts feeling defeated and at risk of injury. My main concern with hip and shoulder flexibility problems in gymnasts is the wrist, elbow, and shoulder injuries.

The Key Points

- Gymnastics is a sport that requires a lot of flexibility and mobility. It’s a major area of training.

- It can be confusing and overwhelming, especially when you consider the rapid rise in scientific advancements and the advent of the internet.

- Before attempting to assign flexibility drills, anyone working with gymnasts needs to be familiar with anatomy and physiology.

- Although the research is inconsistent, it appears that regular flexibility training can increase the range of motion.

- It is crucial to use the correct methods to reduce joint stress and bias stretching of soft tissues structures, particularly in hypermobile athletes.

- Gymnastics has some role for static stretching, but it must be done correctly and in the right amount. When used regularly, other forms of stretching such as dynamic stretching and PNF are effective.

- Gymnasts must adhere to the principle of consistency over intensity.

- Research is mixed, but self-soft tissue care such as foam rolling or other tools could play a role in decreasing soreness and increasing blood circulation to muscles.

- Research supports many other tools, including proper strength training, eccentrics, and managing workloads. These must also be considered and utilized.

- To see progress with flexibility, movement assessments are crucial

- Flexibility programs should include screening, soft tissue care, and stretching.

Background Anatomy and Understanding Hypermobility

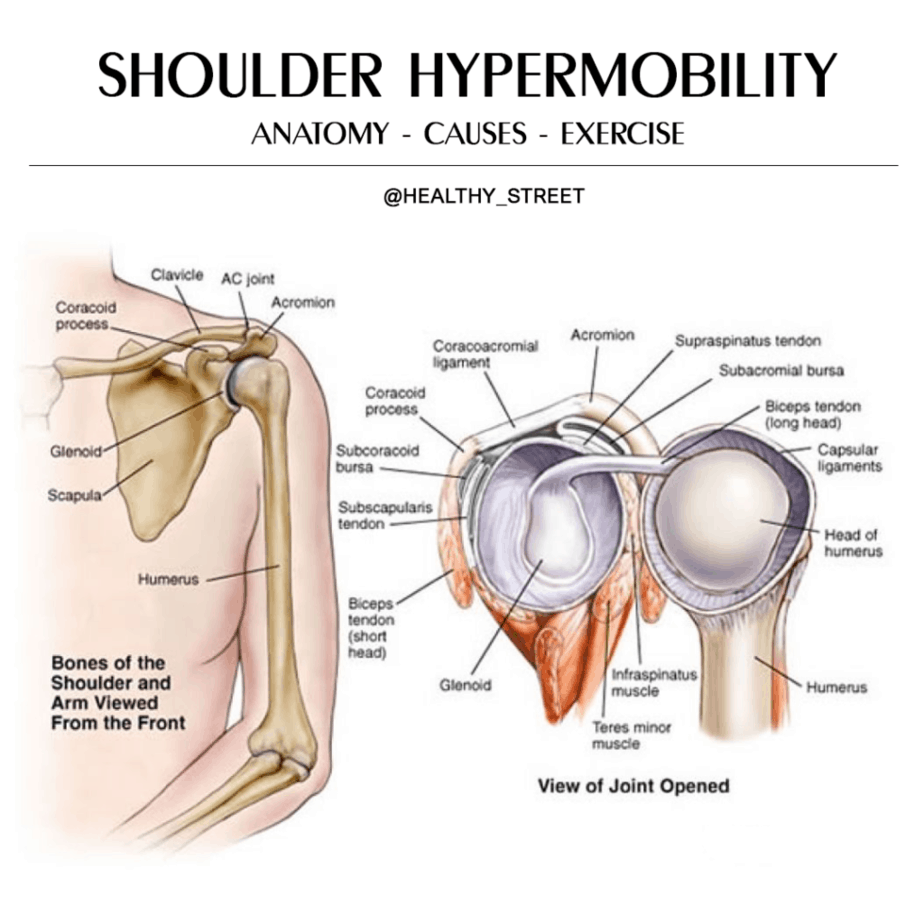

Any discussion I have with coaches and gymnasts about flexibility focuses on basic anatomy. It is important to understand that the range of motion that a gymnast’s hips, shoulder, and other joints show are directly related to their anatomy. There are many structures that can affect how each joint moves. These structures can be grouped into “passive” and “active” categories. Research has focused on the hip, as well as the shoulder.

These passive structures are made up of bones, ligaments, and joint capsules. These structures are stable for the most part, except for surgery or adaptation over many years, as can be seen in children who start overhead throwing or grow up.

Active structures are what we know more about from gymnastics flexibility methods. They include muscles, tendons that connect muscles to bones and the nervous system. These structures and systems are more susceptible to being altered by training. These structures and systems are more likely to increasing flexibility of the hips or shoulders of an athlete.

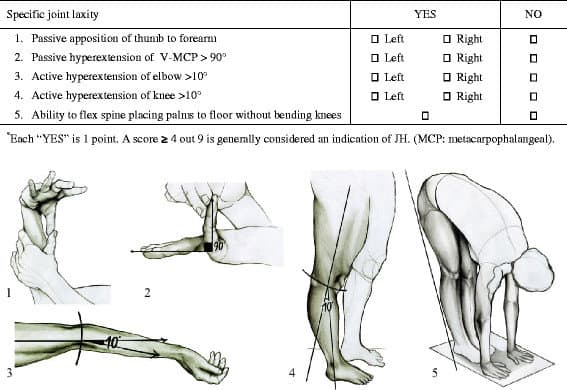

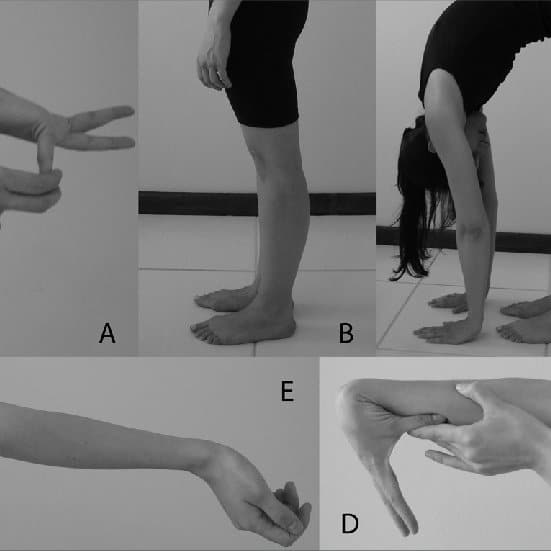

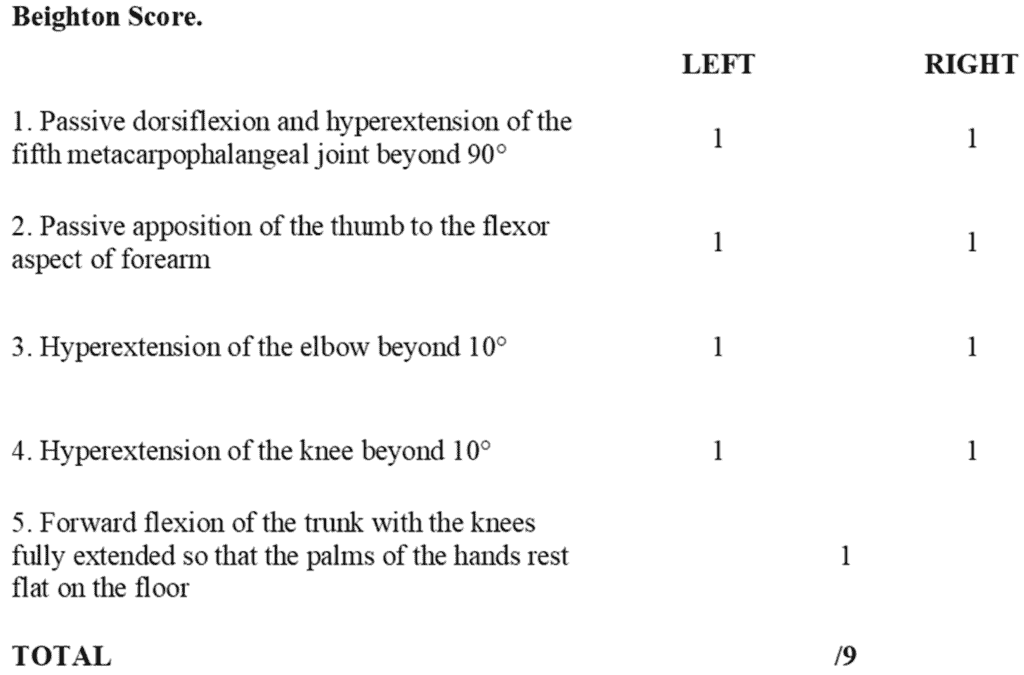

Beighton’s Testing Links and Capsular Laxity

A large number of gymnasts have natural hypermobility. This simply means that the passive structures such as the ligaments and joint capsules are already very loose, so they may naturally have less stiffness. A Beighton screening is used to test this. This screen measure hypermobility by looking at the elbow, knee, and elbow hyperextension. It also looks at the ability to touch the ground in a pike stretch, hyperextensions of the pinky, as well as hyperextensions of the thumb.

Each child’s body is unique and may have certain characteristics that make them more likely to succeed in particular sports. Hypermobile children may be able to excel in sports such as baseball and gymnastics. Basketball and volleyball are great options for naturally tall children. Fast kids might do well in track and field or soccer. Athletes with naturally flexible ligaments can move in specific directions for basic gymnastics skills. Extreme mobility is required to perform handstands, beginner leaps or jumps, as well as introductory ring and parallel bar skills.

These gymnasts enjoy recreational gymnastics from an early age. They are able to use their hypermobility and any talent or coaching to control this range, which allows them to be very successful from an early age. They are able to perform basic gymnastics skills, such as tumbling and bar lines, flexibility drills, and can also create basic shapes. Although this is not always true, the majority of young gymnasts fall within this category once they reach the recreational level.

These children are often identified early in their talent and quickly placed into competitive team tracks. Their flexibility and ability to perform lower-level tasks are something that coaches notice. These gymnasts are often flexible but can struggle to gain strength and power through training. They can make rapid progress if they have more strength and technique training in an organized environment.

Some children are gifted with their bodyweight strength abilities, but they don’t have natural hypermobility. These children tend to be more inclined towards power or strength and less towards flexibility. Although these cases are less common in gymnastics, they do occur. Many athletes are stiffer than I am, but they excel in gymnastics because of their natural power.

This introduction to gymnastics is a “natural selection” style. It provides a foundational idea of flexibility training. We don’t want to put too much stress on athletes’ ligaments and joint capsules, as many gymnasts are hypermobile.

Even if an athlete is not naturally hypermobile, but strong, it is important to avoid putting too much stress on passive structures such as bones, joint capsules, and ligaments. This is one of the most effective ways to increase injury risk and slow down skill progression.

The risk of stretching ligaments or joint capsules without a medical background is extremely high. In some cases, mobilizing these passive structures may be necessary (after surgery or other trauma). This requires highly skilled medical training and must only be done by competent healthcare providers.

To avoid unnecessary strain on the hips and shoulders of gymnasts, we all need to be able to understand and use the best science available. It is difficult to determine whether discomfort reported during stretching is normal and safe.

Flexibility training will bring some discomfort. To some degree, this is normal. There is a fine line between causing real pain and causing discomfort. It is important to distinguish between stretching the correct active structures to improve and stressing the wrong passive structures to inflict injury. I recommend that you don’t stretch with more intensity than 3-4 out of 10. (0 is no discomfort, 10 extreme discomforts). This is because prolonged soreness can indicate microtissue damage.

Athletes may experience some discomfort in certain areas. Other areas could indicate more serious injuries. The discomfort from stretching the hamstrings is usually felt in the middle of the back, and not in the buttocks. This is where the hamstring connects to the open growth plate for pre-pubescent gymnasts. Stretching the shoulders above the head can cause discomfort in the area between the lats major and teres minor. There may also be some chest tissue stretching at the place where the pecs are. The discomfort should not be felt on the top of your shoulders. This could indicate rotator cuff, soft tissue impingement, or soft tissue injury under the coracoacromial area.

There has been an increase in “hip flexor strains,” groin strains, and “cranky shoulder” which I feel is being swept under the carpet in gymnastics. This directly links to the conversation about anatomy and active and passive structures and where discomfort is expected.

Many people assume that athletes who experience pain in their hips or shoulders are suffering from pulled muscles. They tell you not to worry and that it is possible to train through it. This can happen in gymnastics but it is not always correct and may be dangerous.

Many people mistake small strains for more serious problems like labral tears, stress fractures in the pelvic bone, and damage to the rotator or biceps tendon. It is difficult to distinguish between a hip strain and a more serious ligament or labral tear without a thorough understanding of anatomy and injury mechanisms.

These minor flare-ups of pain might not cause major problems in the short term. This could be a minor strain. It may be a minor strain that resolves quickly with a little bit of modification and advice from a qualified physician. These bumps and bruises can sometimes be inevitable in such a high-force sport.

These types of injuries can quickly escalate into major injuries in the gymnasts I treat. What was initially thought to be a pulled Hamstring ended up being a pelvic stress fracture? This required six months of rehabilitation and time off. I’ve seen sore shoulders become rotator cuff injuries and shoulder instability. This required surgery. Also, I’ve seen what was thought to be a hip strain become a major labral tear that can lead to a career-ending injury.

I don’t mean to suggest that all pain reports should be panicked about. Simple muscular strains aren’t common. It can be dangerous to assume that ongoing pain reports are not a big deal and can easily be managed. This can lead to a lack of critical thinking. Let’s now review the anatomy.

Anatomy

You can think of the shoulder joint as a “golfball sitting on a golf tee”. The golf ball, or the ball of the upper arm bone, is naturally larger than the tee (socket or the shoulder).

The bones are the bones, and their shape/fit is often called the first layer of the shoulder joints.

This allows for a wide range of mobility in the shoulder joint but with less stability. This is in contrast to the hip joint which, due to its deeper hip socket (remember that hips are designed for weight bearing while shoulders are not), has greater stability but less mobility.

The “joint capsule”, as well as the ligaments, is found around the socket and ball of the shoulder. It is a cylindrical structure that looks like a balloon and surrounds the shoulder joint. The capsule also serves as a thickening agent for ligaments.

They are further subdivided into the Superior Glenohumeral Ligament (for geeks like me), the Middle Glenohumeral Ligament (for the inferior Glenohumeral ligament), the Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament and the Posterior Glenohumeral Ligament.

The “passive” structures, or stabilizers, are formed by the ligaments, joint capsule, and the alignment of the socket ball with the socket. These structures also serve as layer two in the shoulder joint.

Many people use the shirt sleeve analogy to highlight the joint capsule. If you are wearing a shirt and look at your arm, the shirt sleeve around your arm is the second layer of joint capsules.

The joint capsule and ligaments provide stability. Different parts of the capsule limit certain ranges of motion. As with a shirt’s sleeves, the taught areas of the shirt sleeve depend on the position of your arm in space.

The last ten years of research has revealed a lot about the ligaments and the capsule areas that help prevent the ball from leaving the joint and subluxing.

To return to the example of a shirt sleeve: more mobile athletes (gymnasts and baseball players) tend to have a longer sleeve. Others, who are more rigid and naturally strong in other sports, may have a shorter shirt sleeve. While this allows for greater or lesser inherent flexibility, there are many other factors that can influence it.

It is normal for gymnasts to have some ligamentous and capsular hypermobility. Their natural hypermobility, however, can cause problems as we have seen in previous chapters.

We want not to strain or overload passive structures such as the capsules and shoulder ligaments.

Many in the gymnastics community see it as a professional discussion about removing excessive flexibility methods, following science and subtle training changes.

This is in addition to the fact that the gymnast has an underlying lack of stability from the capsule and ligaments, so they will require absolute strength, physical preparation, and dynamic stability from their muscles around this joint. This will increase strength and power as well as reduce the chance of instability-based shoulder injuries. The muscular soft tissue is the third layer.

Many people are familiar with the muscles of the rotator, triceps, and lats.

Remember that shoulder motion is largely controlled by the upper back or thoracic spine. Gymnast may have difficulty lifting their arms above their heads or behind their backs due to a restricted thoracic spine. To determine if there are any issues with their thoracic mobility, it is important that gymnasts have it checked. I will be sharing more details during the circuit sections.

Hip Anatomy

My thoughts about hip mobility and the reasons we choose certain exercises closely mirror my thoughts on shoulder mobility. I won’t go into too much detail as this topic was already covered in an earlier chapter.

In the past decade, research has rapidly advanced in the area of hip micro instability and labral tears, hip stress injuries, and other injuries common to gymnasts. It was great to hear from so many top surgeons, health professionals, and strength coaches to share their thoughts and discuss what needs to be done.

I encourage you to do your own research on background hip anatomy and current thoughts about hip injuries in the medical or strength field. As it relates to injuries, I will briefly discuss some of the concepts. However, I cannot stress enough the value of the articles and textbooks that I have used over the past five-years.

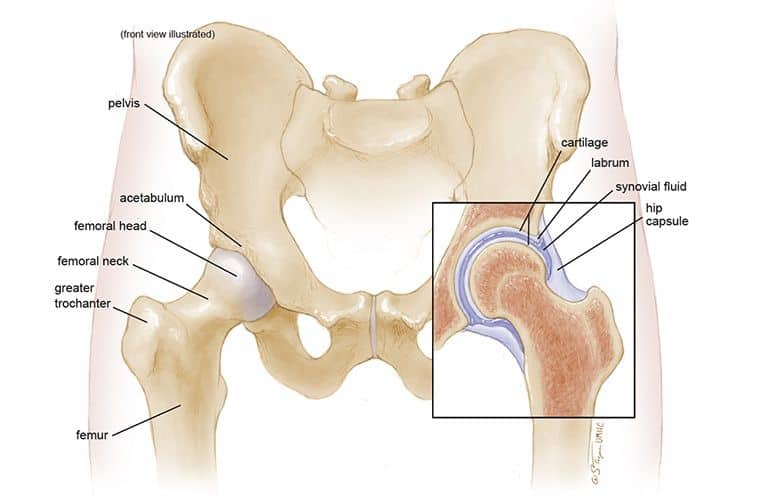

The hip joint, which is parallel to the shoulder and consists of the socket (acetabulum), the upper thigh bone(femur), and the femoral head (femoral head), which serves as the ball.

The socket of the shoulder joint is very shallow. This allows for a lot of motion, but also creates stability. The hip has a deeper socket and more joint congruency. This provides greater weight-bearing stability but can limit hip mobility.

A bony alignment is found in some naturally flexible gymnasts where the hip socket may not be as deep. This allows the femoral head to move in a wider range of motion and creates greater hip mobility in all planes. This gymnast doesn’t need to practice flexibility as much to be able to do full splits. These gymnasts also have hip capsules that are too mobile, similar to the shoulder.

Dysplasia refers to a hip socket that is too shallow.

These gymnasts were made this way. Because they had full splits, and bridges, this is why they were considered a good candidate to compete in gymnastics. As in the shoulder, their hip mobility allows them to move with greater ease. During the training of flexibility, we must be careful not to strain their already hypermobile hip capsules or ligaments.

This mobility requires strength, technique, and exceptional muscle stability. The gymnast is unable to afford limited dynamic protection due to the lower hip socket and natural hypermobility.

Here is where the third layer dynamic stabilizers, muscles and core comes into play. Hip safety and performance are dependent on the glute muscles, deep hip rotations, core muscles, and other hip muscles.

Important to note that athletes can have different bony morphologies of their hips. For example, their hip socket or femur may be more forwardly (anteverted) than backward (retroverted). A gymnast might have a lot of hip rotation and toe rotation, but not much motion.

Another example is that the gymnast might have a lot of hip and toe rotation, but not any moving “toes out.” This makes it difficult to determine if the gymnast falls into one of these categories. A boney congruency can also be seen with the help of X-Rays and advanced medical imaging. A combination of dysplasia and hip socket rotations, hip rotations, femur rotates, or different pelvic alignments may be present in some people.

Although it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss all the anatomical variations, the reader should be aware that not all gymnasts have the same hips. The gymnasts with naturally mobile hips and flexible hips are often the ones that we see being used to demonstrate during speaking presentations, clinics or videos online.

Because she has unique hips, it is unlikely that this gymnast will have difficulty doing a flexibility video online. This same drill could cause severe pain and restricted motion in another gymnast with very shallow or retroverted hip joints.

Many gymnasts are limited by their bony alignment, different shaped hips, or less mobile capsule/ ligaments. They may not be trying hard enough. A gymnast who is naturally mobile may have difficulty applying a general stretching exercise in a presentation might be able to do it all.

To push through a bony or ligamentous restriction aggressively will only result in pain and headaches for everyone. This concept can be helpful for anyone who is still struggling with hip mobility. For a complete assessment, take them to a qualified physician.

Conflicting research on Foam Rolling and Soft Tissue Care

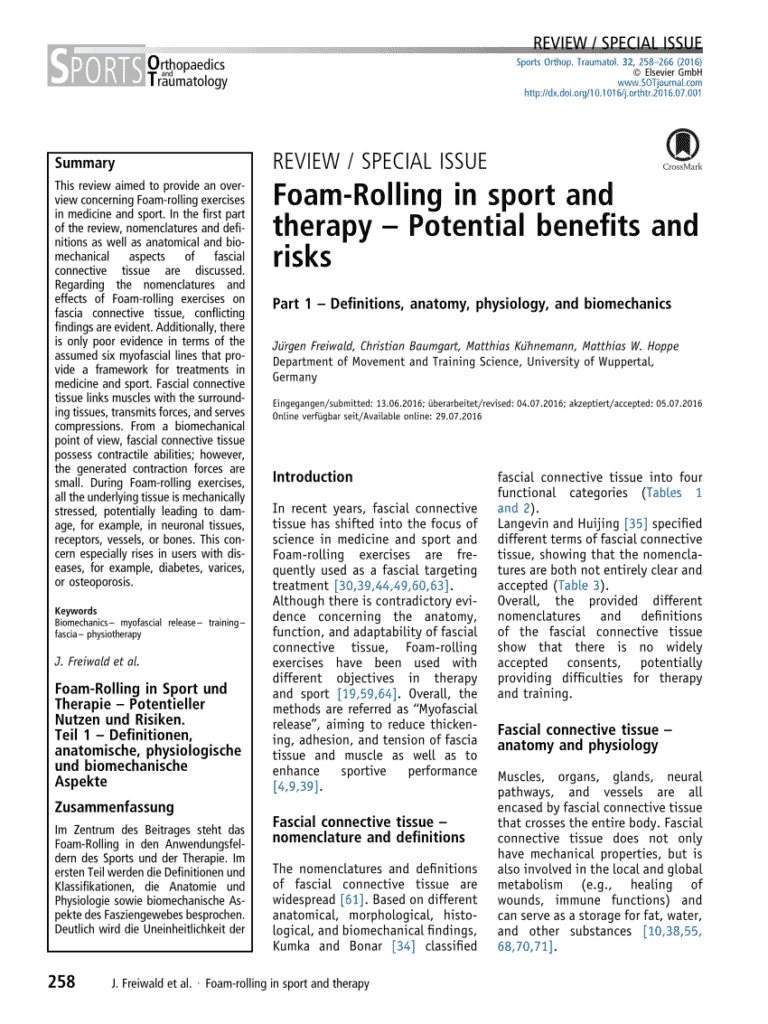

Research has not been consistent on the long-term changes in range motion that can be induced by stretching techniques and self-soft tissue therapy. Although there are some short-term changes in range motion, these tend to not last for long without consistent strength training or regular practice of flexibility.

In 2015, Jakob Skarabot and Chris Beardsley reviewed a number of studies to find that foam roller use “appears” to cause acute increases in flexibility. However, some studies did not report any significant changes in the range of motion after foam roller use.

The types of tools, pressures, duration, and instructions were given to the study participants could all have a bearing on conflicting results. A review of the literature revealed that self-myofascial release combined with targeted static stretching could result in the greatest benefits to acute flexibility changes.

Because of the research results foam rolling, stick, or other forms self-massage has on gymnasts, I recommend it often as part of their flexibility training. Self-myofascial relief can be a very effective strategy when combined with other strategies and based on movement assessments.

My preference is for gymnasts to apply moderate pressure, which does not cause pain, for between 10-30 seconds per muscle, away from bony regions. Because a lot of manual therapy and self soft tissue work doesn’t recommend intense pressure or foam rolling for its positive effects, this is because there are many other options.

My experience shows that excessive force, excess duration, and incorrect placement of a stick massager or foam roller can all have adverse effects. This research is important for coaches, gymnasts, as well as medical professionals, to understand.

Some coaches are concerned that foam rolling or static stretching before training could negatively impact strength and power output. This concern is based on research findings.

Recent research supports the notion that foam rolling and dynamic warm-ups before training do not have any significant negative effects on performance. They may actually enhance it and positively impact various muscle groups. (49-50). This is based on self-myofascial release literature reviews and manual therapy literature reviews. It may be due to changes in perceived soreness or neurological relaxation.

Beardsley and Skarbot presented the following:

“Self-Myofascial Release does not appear to impair athletic performance in the acute or short term. This section had slightly lower quality than overall review studies. Except for two cases (Janot and Peacock, 2013; Peacock and et. al. 2014), there were no performance changes following any of the SMFR protocol used.”

All the science and discussions I’ve had with doctors about stretching or self-myofascial therapy have shown that foam rolling can have a positive effect on performance when applied correctly. My experience working with hundreds of gymnasts to improve flexibility supports this. Regular stretching and foam rolling are recommended for the improvement in range of motion, perceived soreness, and recovery. There are minimal adverse effects on performance. These tools should be used in conjunction with full dynamic warmups and technical drills that are common in gymnastics.

It is important to stress that proper stretching and soft-tissue work are not the only way to increase flexibility and performance in gymnasts. This is just one part of the puzzle. It must be used along with strength work, movement assessments, technique work, consistent practice, periodization programs that calculate work-to-rest ratios, and movement assessments. These are the topics I tend to write about and speak on most, as they are often misunderstood or underrepresented in gymnastics. It is important to combine science with coaching expertise and consistency in training.

Many of the injured sportsmen that I treat report that soft tissue massage makes them feel warmer and reduces muscle soreness. It is also beneficial for recovery after hard training or light training. Many claim it allows them to move with a greater range of motion and less discomfort than before they start their practice. Some very inflexible gymnasts I’ve worked with showed improvements in their hip and shoulder range of motion when they combined soft tissue work with proper stretching/strength programs.

As a healthcare provider, manual therapy is something I do regularly to treat injuries. This is based on a complete medical assessment. As with the warm-up concept, it is just one part of a larger puzzle for increasing hip and shoulder flexibility over time. In a matter of a few sessions, I often notice a significant change in range of motion. This is assuming that the gymnasts are committed to the home program.

Many gymnasts will continue seeing me during the competitive season as maintenance care. They can see how stiff and adaptive they become from competing or training high volumes. This was something my mentors stressed to me, and I have adopted it into the practice of working with sportsmen. These are only anecdotal stories, but they correspond with the literature.

Although I acknowledge that there is some controversy in the theory and practice of soft tissue work (and it does seem to have some positive effects), I still support its use. There are many different views about soft tissue work. It takes very little time and doesn’t seem to have many negative consequences if done correctly. It is a tool that allows sportsmen to perform strength, technique, control, and other skills.

I recommend that people learn more about the practice, research, and use of self-soft tissue work. This information can be shared with healthcare professionals who are skilled in teaching the gymnasts or providing in-services.

Top Stretches for More Flexibility

1. Standing Quad

Quads refer to the quads, which are large thigh muscles responsible for running and jumping. Standing quad stretches can help your child loosen up and increase their range of motion. Begin by having your child extend one leg behind you and grasp the top of their foot. Then, bring it to their rear. This will ensure that the stretch is effective. For better balance, if your child has difficulty keeping their balance, you can let them use a chair or wall.

2. Hip Flexors

Hip flexibility is a key component of gymnastics. It makes it possible to do artistic and physical moves with ease, as well as improving your child’s physical stability.

Your child can stretch their hip flexors by lying on their back with both legs straight ahead. Next, bend one knee and bring the heel to their waist. Keep moving it forward until their hips permit. It’s some facts, what you need to know about hip flexors.

3. Back Twist

Stretching the back properly can reduce muscle strains from the physical demands of gymnastics. Your child should lie flat on their back, include things like with their legs extended in front. Next, have your child bend their knees and slowly lower their knees so that they can complete the stretch. Repeat the motion on the opposite side.

Common Hip Flexors of Concern

Another example of hip flexibility is the way a gymnast’s lower back is when they do quadriceps or hip flexors muscle stretching. The most common stretch in gymnastics involves an athlete’s lower back being too arched or their pelvis tilted forward.

Similar to the shoulder. When you examine the anatomical, biomechanical science and hip joint, hip ligaments and hip flexors, quadriceps and hip flexors, you will see that the hip joints, hip ligaments, and hip flexors are more biased toward this stretching position. It may cause the ligaments and capsules on the underside or front of the hips to take more strain. These ligaments include the medial and sidearms of the iliofemoral and pubofemoral iliofemoral ligaments.

Parallel to the above points, it isn’t that this stretch is necessarily dangerous or bad for a gymnast. This stretch may be used for choreography and drills. It can be used in the right context to increase flexibility for advanced jumps and jumps, Inbar skills, or tumbling mechanics.

It is possible to target the hip flexors or quad soft tissue. Another alternative, based on anatomy, would be to flatten both the spine and the pelvis and then do a similar stretch with core/glute involvement.

Although it doesn’t look as impressive, it is still very specific to what we want to accomplish: to affect the active structures and minimize stress on the passive.

Sometimes, the complexity of research suggests minor adjustments during training. As you can see, the above examples are good examples. It is possible to make small changes in the types of stretching that are biased towards the correct structures of your hip or shoulder, which can result in a significant improvement in flexibility and decrease injury risk. You can do this by using “addition and subtraction”, which means that you use an alternate exercise or change the alignment of some common gymnastics stretches. Global training design changes that involve large-scale changes may require more work.

Similar to the shoulder, extreme hip flexors stretching techniques from very high surfaces, or coaches pushing aggressively on sportsmen are not appropriate. I’ll talk about oversplits further below. However, I believe that there is a lack of education on this topic and why so many people use aggressive methods. There is an easier way, safer and with solid science support.

What makes Flexibility Training work?

It is important to remember that training flexibility should focus on the structures with the greatest potential for improvement. These include the muscles and, to a limited degree, the tendons connecting muscles to bones. The nervous system is also included. Regular stretching is the best way to increase the flexibility of active structures.

Gymnastics and other sports have had stretching for many decades. There are many different ways to practice gymnastics. There are many methods that can be used in gymnastics training. These include static stretching, dynamic stretching, and “active flexibility”. There are many misunderstandings and confusions surrounding what happens to sportsmen when they stretch, why it increases range of motion, how much stretching can be beneficial to increase flexibility, and how to make skills changes.

I will briefly explain the current research in stretching and outline some of the important studies. After I get into the details, I will give a summary of “practical applications” for those who are interested in learning more.

Stretching, in its most basic form is simply extending a muscle beyond its limit of motion and holding it there for a time. This can be done statically (static stretching) or with momentum and holding the end range (dynamic/active stretching). Sometimes, it is combined with muscle contractions and stretching together (“PNF” or proprioceptive neural facilitation).

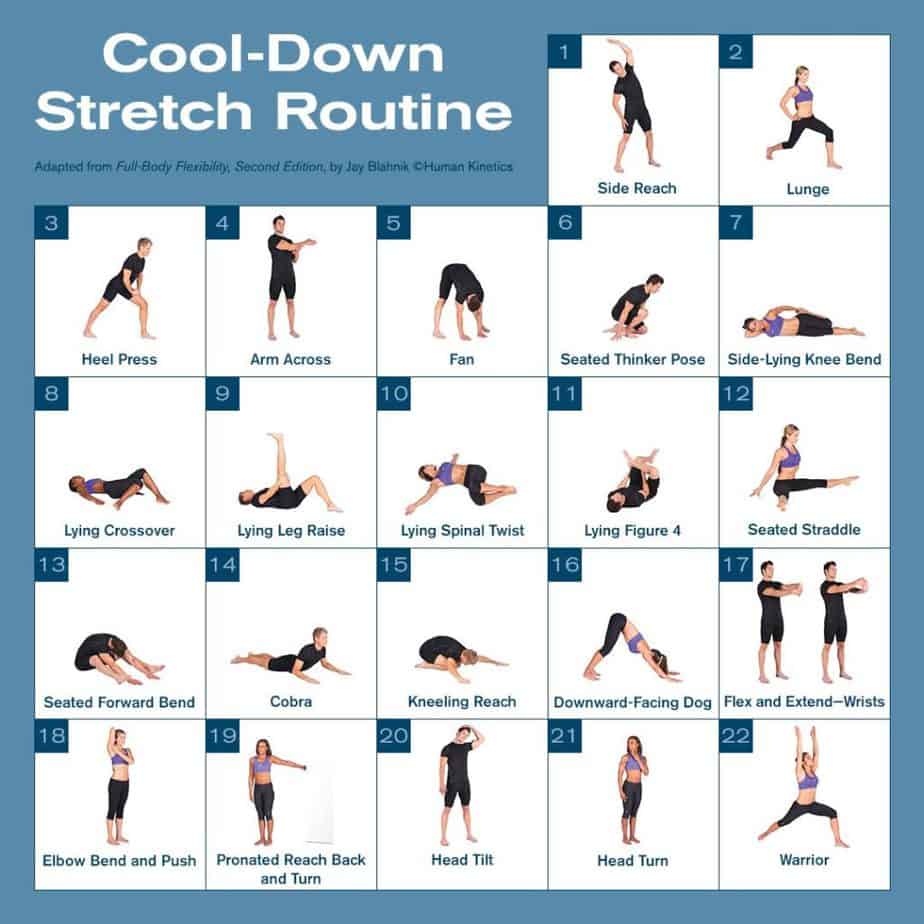

What about Warm Ups and Cool Downs?

When discussing flexibility, another topic is warming up and cooling down. Many people are interested in finding out the best approach, whether static or dynamic, is there a way to increase the range of motion? What drills work best? My view is that the goal of flexibility work must be discussed. Sometimes we just want to get the body moving, while other times we want to increase our joint range of motion. This is how I see the various goals of flexibility.

- Warm up – Get ready to train.

- Flexibility Circuits – Step by step circuits are used to improve joint mobility or flexibility. (more below).

- Cooldown – Allow the body to slowly recover from a tough training session. It is not the best time to increase joint movement, since the body is often in a high-stress state after a hard training session.

The warm-up shouldn’t be considered the time when we want to make major changes in flexibility. Warm-ups can be viewed as a time to prepare for the joint range of motion required by a gymnast. Warm-ups are often large and take up a lot of time. You should also remember that you will be genetically exposed to very high forces immediately after the warm-up. We don’t want to relax muscles and increase joint motion, then we expose them to very high forces. The warm-up is a preparation for the training session.

These concepts are covered in a lot of literature (38-40), but I believe a multi-step warm-up is the best way to achieve this goal. Before practice, athletes should do light soft tissue preparation or specific areas of focus. Next, do a joint-based preparation. Finally, do a full dynamic warm up. After a full-bodied dynamic warming-up, athletes can do core basics, jumping, landing basics, and other gymnastic-specific prep work before moving on to the first about. Here is a video showing the entire warm-up.

Cooldowns are what most people associate with gymnastics. To help calm the body, we will ask our gymnasts to do a short foam roll (or light stretch) for 5-10 minutes. The theory is that the body will shift into parasympathetic mode, which can help to clear some of the acidic byproducts and metabolites from training. Also, the body will experience more blood flow than if it were just sitting down and walking out of practice. Specific flexibility circuits are those that I believe offer the greatest potential to make positive changes in joint flexibility. These will be covered in detail below.

To increase flexibility and body strength, 10 toddler tumbling games

How do I get my kids to tumble?

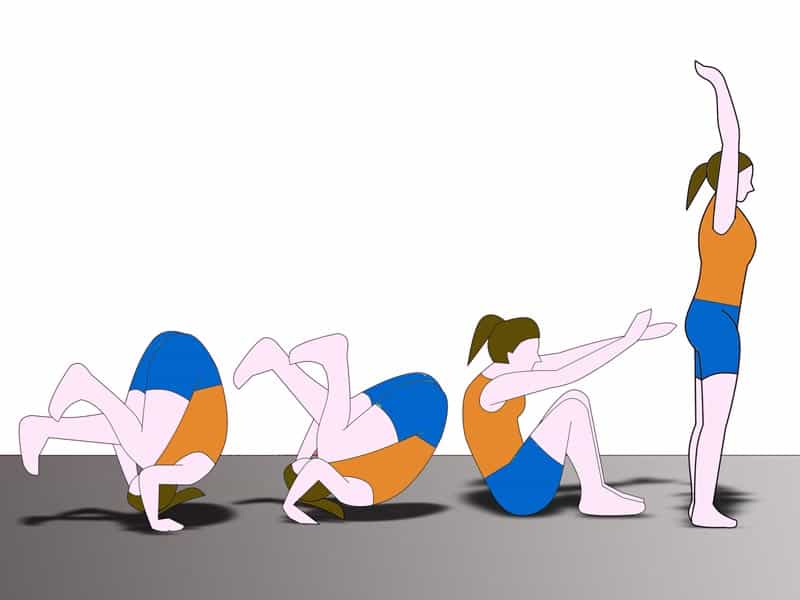

Start with the basic skills of tumbling: the forward roll followed by the backward and cartwheel rolls.

Once they have mastered these skills, they can then move on to the round-off, which is the most popular skill in the sport for young athletes.

As they improve in tumble, the number and variety of turns and rolls in each run increase, making the sport more thrilling.

Tumbling Equipment

To perform tumbling, all you need is a space with a gymnastics mat. This usually happens in a gym.

To aid competitors in competitive tumble, a 25-meter-long sprung track is used.

For beginners, trampolines and springboards are also great tools to practice and learn aerial skills before taking them to the air.

Safety tips

Although tumble is a fun game, it can also be dangerous if you don’t take it seriously. These safety tips are important to remember:

- Before you move on to more advanced skills, it is important that you understand the basics.

- Before you start your tumbling exercise, warm up properly. Then stretch at the end.

- The best way to learn is to perform tumbling in a matted gymnasium under the supervision of qualified coaches.

Learn more about Safety Tips during Activities and Exercises for Kids.

1. Forward Rolls/Somersaults

Split the group into two or three groups and let the players pick their partners.

Tell your children: Start in a crawl position and tuck your head under your chest. Next, push your bottom upwards and over until your body rolls over.

To keep your partner’s chin down, push your partner’s bottom and place your hand on the top of his head.

This exercise can be repeated five times.

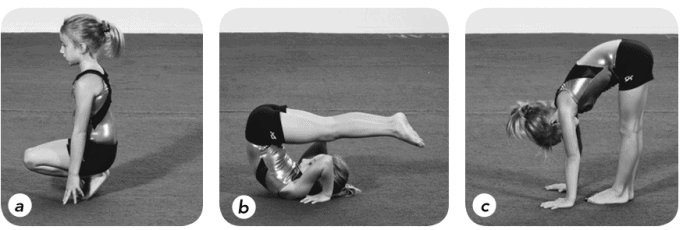

2. Backward Rolls

Split the group into two or three groups and let the players pick their partners.

If young athletes are learning how to backward roll, show them the move and then teach them.

It is possible that they will need to be assisted by an adult or another partner at the beginning so that they feel the movement.

Tell your children to sit on a mat at the edge with their knees bent and their chin in your chest.

Place your hands on either end of your head, palms facing up.

Your partner can help you by placing one hand on top of your head and one on the bottom.

Rock backward and forwards, while keeping your tucked position.

You will gain confidence as you rock harder until your hands touch the mat.

Change your starting position when you feel comfortable.

Instead of sitting down, tuck your legs while standing up straight.

Continue rocking from the starting point until your break is over.

As a protection for your neck and head, keep your hands still.

To complete the backward roll, push your hands hard when your hands touch the mat.

Your partner can help you by using your hips to support your hand. You should practice the backward roll many times.

You will gain confidence as you move. Start by placing your hands on the mat. Then, slowly raise your hands up to your ears and rock backward. Do 5 Backward Rolls.

You will see improvements in your form and speed with practice.

3. Cartwheels

The young athletes do a cartwheel by moving sideways in a straight line.

He straightens his back and places his hand on the ground. Then he moves to the other side.

His legs cross over his body, then he lets his hands and body fall.

You can perform a cartwheel with one, two, or none hands.

It’s a sideways motion. Therefore, it doesn’t matter if the legs are bent or straight. As long as the body is in a sideways movement.

Then tell the children to do a cartwheel and a lunge.

The stronger leg leads the lunge and the weaker is at the back.

When you lunge, lift your arms straight up in the air while keeping your hips aligned with the front.

Place your forearm on your back and your hands shoulder-width apart, or wider, on the ground in front.

You will find your body inverted as you kick your legs upwards and cross your torso.

Your legs should remain straight while you rotate. Your feet and toes should be pointed.

Your first foot touches the ground. The second foot follows. Land in a lunge position with the lead leg in front and the weaker leg behind.

This exercise can be repeated 10 times.

4. Assisted Handstands

Split the group into two or three groups and let the players pick their partners.

Tell your children: Get your partner to hold your ankles in a handstand or grab a wall to keep you balanced and improve your upper-body strength.

Keep your feet about three feet from the wall, and raise your hands high above your head.

Keep your arms straight, touching your ears and stepping forward.

You get more momentum from the kick.

You can kick one leg in front of the other and then take a big step forward with it as far as you feel comfortable.

From your fingertips to your back foot, keep a straight line.

Keep your back straight while leaning forward. Use your back foot and lunge to push forward.

Common mistake: Toss your hands down on the ground, and then try to lift your legs up.

This causes you to fall forward and results in a whip at your top.

When your hands touch the ground, ensure that your arms are straight.

For support, your legs should touch the wall. This exercise can be repeated five times.

5. Round-Offs

Explain to the children that a round-off is similar to a cartwheel, except that you land with both your feet on the ground and not one foot at once. You face the direction you came from.

You can do this by twisting your shoulders and placing your hands on the ground.

You should place your hands one after another. Kick your feet up and bring your legs together.

This exercise can be repeated 10 times.

6. Solo Handstands

Children should be taught to stand straight up and raise their hands high above their heads.

Keep your arms straight and your ears close to your ears. Move forward, then lower your arms and throw your hands back.

This gives you more momentum. You can kick one leg in front of your body and move forward with it as far as you feel comfortable.

Keep your body straight from your fingertips to your backfoot.

Keep your back straight while leaning forward. Use your back foot and lunge to push forward.

Common mistake: Toss your hands down on the ground, and then try to lift your legs up.

This causes you to fall forward and results in a whip at your top. Keep straight.

When your hands touch the ground, ensure that your arms are straight.

Do not let your shoulders slump or bend at the elbows.

You can inflict injury on yourself if you bend your arms. This will allow you to maintain balance.

If you feel the majority of your weight on the palms of your hands, try to keep it at the base of your fingers.

This allows you to push backward or forwards with your hands, to compensate for any kicks that are too hard or too slow.

This may take some time before you find the right balance.

You will soon be able to get it almost every single time. Keep all your weight in check. Straighten out completely.

Once you have successfully completed the handstand, it is important to keep your head in neutral and your back straight.

Instead of focusing on your eyebrows, look at your hands. This will help you see your hands and not throw your head back.

Ten seconds of handstand practice is recommended.

7. Backbends

Props – Soft pillows or a rug for each pair

Split the group into two or three groups and let the players pick their partners.

Tell your children: Start a backbend by laying your legs shoulder-width apart.

Slowly do this gymnastics exercise. Don’t fall backwards into a backbend.

Be calm and patient.

You can try it if you’re not familiar with the technique. Have a partner hold your waist and help you practice getting into a backbend position. This will prevent your core from collapsing.

Place your hands on the ground with your arms straight up. This exercise can be repeated three times.

Note – Working in pairs, one person may serve as a spotter. This is particularly helpful if your partner is an adult.

8. Backbend Kick-Overs

Tell your young athletes to get into a backbend and then kick your strong leg up.

Keep your weaker leg behind it.

To complete the task, jump with the leg that isn’t moving over.

Land with your arms raised and your feet together.

This tumbling exercise can be repeated three times.

9. Stay Within the Lines

Props – A roll of easily removable tape

Tape two lines across the floor. These lines should be at least 12 inches apart and approximately 10 feet in length.

Talk to your children about practicing Forward Rolls/Somersaults (#1) within your lines.

You can travel through the lines ten times.

Variation – Once you have mastered this skill, reduce the distance between lines by an inch each time until they are just 6 inches apart.

10. Leg Splits

Tell your young athletes to sit on the ground with their legs straighten and their toes pointed.

Try to bring your nose as close as possible to your knees. This position should be held for 30 seconds.

Next, flex your feet while still keeping your nose as low as possible.

Once you’ve done that, take a wide straddle position and place your elbows on the ground.

For 30 seconds, hold this stretch and extend your arms. Then reach as far as you can with your hands.

Try to get as close to the ground as possible.

Continue for another 30 seconds.

Next, place one leg in front of the other and squat from your knee. Your rear knee should be on the ground, your front foot should be far in front.

For 30 seconds, hold the position and then relax. Next, lift your front leg and place your nose on your knees.

Slide as far as possible into the split. These stretches can be repeated on the opposite side. Each position should be held for 30 seconds.

do not bounce when you are stretching or pushing yourself, even if it is painful.

Why Do Gymnasts Lose Flexibility?

Although there are many opinions on the topic, I have narrowed my thoughts to three key contributing factors to why gymnasts might become stiff while participating in gymnastics.

- Natural Growth The main reason for this is that most people who participate in gymnastics are young children who are still very much in their youth. Their chronological age is not always the best indicator of their growth rate. They often experience different levels of growth spurts. Different gymnasts develop at different rates and have different growth spurts. Because the tendons, muscles, and nerves are stretched, this causes limited range in hip, shoulder, and ankle motion. This is often seen in athletes who have difficulty with flexibility and feel awkward during training. There is an adjustment period. Communication, flexibility work, constant flexibility work, and ensuring there is a great strength and conditioning program are all key factors. This brings me to my second point.

- Strength Training Programs that are not balanced – I’ve had the opportunity to evaluate hundreds of strength and conditioning programs in both my consulting and coaching career. These include non-competitive, competitive, and collegiate teams as well as internationally elite ones. One thing I see consistently is an imbalance in the training of certain muscle groups. The quads and hip flexors are often trained at a higher percentage than the glutes, hamstrings, and external rotators. The chest and lats in the upper body are significantly more than the scapula, upper back, and rotator sleeves. Although this is a topic that will be discussed at another time, it is due to a stubborn culture that does not accept the external loading of gymnasts with dumbells, kettlebells, or barbells. You can easily cause imbalances in the hip and shoulder joints by using dumbells or kettlebells for basic movements like deadlifting, hip lifts, and upper back rowing. This is what I believe is the biggest problem for athletes who struggle to achieve long-term flexibility. I am also concerned that gymnasts are being criticized for not being flexible. Instead, the programs they are participating in are treating stability issues using a combination of strength and flexibility programs. They are not using scientific evidence to support their flexibility. There are times when an athlete should put more effort into flexibility and strength training, but I believe that we all need to take responsibility for our actions and realize that we may be contributing to the problem.

- Adaptations for Training – As I mentioned, gymnastics involves a lot of repetitive motions. To learn the foundations of many skills, drills, and other technical training pieces, you must repeat the exact same movements over and over again. This is also true for young athletes in other sports. Muscle stiffness adaptations are often associated with repetitive training. Baseball players are known to have decreased overhead flexibility and shoulder internal rotation as a result of muscular soft tissue stiffness. Many runners complain of stiff calves after running for hundreds of miles over a period of time. While it has not been proven in a gymnastics study, I believe that gymnastics exposes athletes to repetitive motions that cause soft tissue stiffness. They can cause flexibility loss if not addressed immediately. Gymnasts use their inner thighs, quads, and calf muscles to keep their form. They also run, hurdle, kick and make shape changes. The upper body’s lats, teres minor, and packs are used to maintain good shapes and power the equipment by shape-changing.

These three areas are combined with the previously discussed points about gymnasts not being able to use the best science to stress muscle tissue and spare joints capsules to improve flexibility, making it easy for them. Although puberty can have a significant impact on flexibility, the cultural expectation that gymnasts will become more rigid as they age is not true. This could all be avoided if there was better flexibility, strength, or soft tissue care.

F.A.Q.

Does Gymnastics improve flexibility?

Regular gymnastics can dramatically increase flexibility. Gymnasts can do a wide variety of moves without injuring themselves or their joints. Young gymnasts have stronger ligaments, tendons, and joint flexibility.

How do you improve a child’s flexibility?

Running is a lot so your child should stretch their hamstrings. Touch their toes with one shoe and pull the heel towards the back. Butterfly stretches on the ground are great for mobile hips.

What is an example of flexibility in gymnastics?

Different sports require flexibility in different parts of the body. Hip flexibility and shoulder flexibility are essential for gymnasts in order to perform many skills. Hip flexibility is essential for jumps, splits, and leaps. For bridges, back handsprings, and many other skills, shoulder flexibility is essential.